Review by Mark Bourne

Q: "After you've done the last stunt, the last kick, what do you want the public to remember about Jackie Chan?"

A: "I just want that one day, when I retire, that people still remember me like they remember Buster. I really want someone to respect me the way they respect Buster."

— From an interview with Jackie Chan, 1997

"When Rob (Cohen, director) set this film (Daylight) up, he was very conscious of what Buster Keaton did — those extraordinary visuals. If you look at Keaton today, I'm in awe of what he did, really in awe of the bravery and the audacity and the temerity."

— From an interview with Sylvester Stallone, 1996

Everything I need to know about life I learned from Buster Keaton.

Take The General, for instance. Like Chaplin's The Gold Rush, Keaton's practically perfect 1927 Civil War masterpiece is a comedy of epic scale and ambition. Moreover — this point is often overlooked — it departs from Keaton's earlier shorts by delivering not a gag-a-minute string of slapstick setpieces, but instead an action-adventure-historical-war-espionage thriller deftly spiced with comic bits. And as Walter Kerr wrote in his indispensable The Silent Clowns: "As The General is the most insistently moving picture ever made, so its climax is surely the most stunning visual event ever arranged for a film comedy."

Set at the outbreak of the War Between the States, one of the film's famous sequences involves a chase between two steam locomotives. One of them is the General, the engine beloved by its engineer, would-be Confederate soldier Johnnie Gray (Keaton). Union Army spies have commandeered the General to use it as a moving sabotage platform against the Confederate forces. Worse, they've kidnapped Johnnie's second great love, the girl Annabelle Lee. Earlier she rebuffed him after a misunderstanding branded him a coward unwilling to join the Confederate Army like all honorable Southern men. Now Johnnie is giving chase in another locomotive, the Texas, determined to defeat the saboteurs, take back his engine, and (possibly in this order) rescue the girl whose tintype he displays in the General's cab.

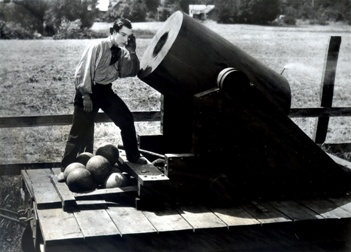

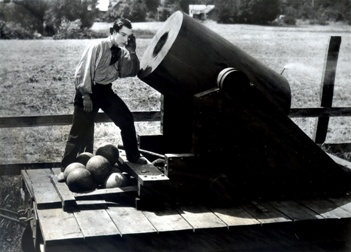

In hot pursuit, Johnnie clambers over the General's fuel tender onto the flatcar holding a cannon he acquired en route. He measures a handful of gunpowder in pinches, then tamps it down, loads the cannonball, lights the fuse, and returns to the engine's control cab. The cannon fires and the cannonball arcs (rather delicately) to his feet in the cab. Giving it that famous deadpan Keaton look, he rolls the cannonball off the speeding train shortly before it explodes.

In hot pursuit, Johnnie clambers over the General's fuel tender onto the flatcar holding a cannon he acquired en route. He measures a handful of gunpowder in pinches, then tamps it down, loads the cannonball, lights the fuse, and returns to the engine's control cab. The cannon fires and the cannonball arcs (rather delicately) to his feet in the cab. Giving it that famous deadpan Keaton look, he rolls the cannonball off the speeding train shortly before it explodes.

He tries again. This time cool-headed desperation prompts him to forgo handfuls and pinches to shove the entire gunpowder keg down the barrel. He loads another cannonball and lights the fuse. His retreat to the cab is interrupted when the flatcar's hitch snags his foot. Shaking the foot free, Johnnie also shakes the cannon barrel down to aim not overhead toward the Union saboteurs ahead of him, but straight at himself and the engine. Now he retreats to safety by climbing the exterior of the engine to the cowcatcher up front, train track blurring mere inches beneath him, Union soldiers not far ahead, and a mammoth cannon aimed at the locomotive against his back. At the critical instant, the track curves just so, the cannon fires, and the blasting cannonball arcs not into the Texas but into the rear boxcar of the stolen General. The explosion leads the frightened Yankee raiders to believe that they are being chased by an outnumbering Confederate militia.

In response, they block the track first with the damaged boxcar (Johnnie cleverly switches the rails to avoid a collision) and then by dropping large wooden railroad ties onto the track. Johnnie slows the Texas and runs ahead to lift the first log off the track. The Texas's cowcatcher catches him like a spatula, and he straddles it with the heavy railroad tie still in his arms. A second tie blocks the track head, and — here's the beauty part — when the Texas approaches it he lifts the first tie and, with Olympian style and precision, heaves it onto the end of the second tie, catapulting it smoothly up and out of his trajectory with neither log clobbering him in the head. The chase can continue.

Like all great movie sequences, it's better watched than described. But in that scene lies a metaphor, I'm sure of it. It's classic Keaton, displaying the qualities that make the "stone-faced" Keaton character forever memorable: his steady resolve in the face of obstacles, his willingness to accept surprises and sudden changes of plan with dry aplomb, pausing only to perhaps slightly arch his eyebrows or momentarily stare the conundrum full in the face. It's as if tattooed on Keaton's chest is a motto taken from Kipling's Barrack Room Ballads: "When first under fire an' you're wishful to duck ... Be thankful you're livin', and trust to your luck / And march to your front like a soldier."

On the great railroad track of life, if only we could address our obstacles with such stoic resourcefulness focused on what we need to do rather than on the mugging-for-the-camera, hammed-up Oh, shit! of it all. Adding to this chicken soup for the movie-lover's soul, remember that we're watching Joseph Frank Keaton, actor and director, performing dangerous and outrageous stunts with no camera trickery or a stunt double because that's what it took to do the job. We can wish for a blip in the zeitgeist that manifests as people all across society — from the loftiest CEOs to the lowliest movie reviewers — finding their bliss and reducing their blood-pressure with one four-letter mantra: WWBD. What Would Buster Do?

* * *

"In a way his pictures are like a transcendent juggling act in which it seems that the whole universe is in exquisite flying motion and the one point of repose is the juggler's effortless, uninterested face." — James Agee, "Comedy's Greatest Era"

* * *

Or how about Steamboat Bill, Jr.? This Mark Twain-like tale from 1928 is Keaton's last great feature. In it, Buster is a ukulele-strumming Harvard milquetoast who returns to Mississippi to find his father, a tough and crusty sidewheeler steamboat captain. In the film's famous climax, the local port town is blown to smithereens by a cyclone. In terms of sheer physical damage, it's an amazing scene. It supersizes stunts and gags Keaton successfully rehearsed in earlier shorts such as "Back Stage" (made during his fruitful years with Fatty Arbuckle) and "One Week". It's the sort of destruction that nowadays would be consigned to CGI. Buildings peel apart and tumble down to splinters at Junior's feet. Houses lift off their foundations. Junior rides a wheeled hospital bed and flies through the air clinging to a tree uprooted and set sailing as if to Oz. A dozen impressive large-scale visual feats come, bam-bam-bam, in this scene alone. And through it all his expression, as ever, registers only controlled alarm and a certain thoughtful interest in the forces buffeting him hither and thither.

"What Keaton did physically is actually quite startling when you discover that he did all of his own stunts," said Kevin Spacey in a 1999 American Film Institute special. In the cyclone scene, the stunt everybody talks about in the falling house, perhaps silent cinema's most memorable death-defying image. The two-story, two-ton facade of a house descends to squash Keaton below. It smacks the ground and shatters, with Keaton saved by standing in the precise space of its small open window. Spacey again: "The famous one is when the house falls. He had to stand on a mark. I'm told it was a nail ... if he moved an inch to one side he would have been crushed to death."

Again, St. Buster teaches us that, in a world of windswept and sometimes violent unpredictability, we can either teeter face-first into the gale and risk sliding through the mud on our ass, or allow life's vicissitudes to carry us where we must go to (in Junior's case) save the day, embrace reconciliation with our loved ones, and get the girl. When the walls are falling down, WWBD tells us: stand where the window is.

Never mind that The General is based on a true story and shows off Keaton's fanatical devotion to historical authenticity. He filmed it in Oregon for the scenery and because only there could he find the narrow-gauge track required for the genuine period locomotives he acquired. The beautiful Mathew Brady-inspired photography includes luscious moving long shots of vast forested mountainscapes, steaming locomotives (the coolest comedy props ever used), and warring Northern and Southern armies played by hundreds of Oregon National Guardsmen. Never mind that its most famous moment, the aforementioned "most stunning visual event" in which a real, full-sized train plummets off a burning high-span trestle bridge, is the most expensive shot from the silent era — $42,000, equal to almost $2 million today. It goes without saying that there were no second takes. (The wrecked hulk of the locomotive remained in the river near Cottage Grove, OR until it was dismembered for scrap metal during World War II.)

Never mind the comedic, dramatic, technical, and filmcraft sophistication on view throughout this disc. No, the fulcrum point of both The General and Steamboat Bill, Jr. is Keaton's signature image — a man alone, making the most of whatever the hell's going on around him.

* * *

Watching Keaton today, we realize that he's the most modern of all silent screen masters. His ongoing travails at the whims of The Machine — meaning his beloved mechanical contrivances as well as Nature or "the Establishment" — make him our contemporary. By virtue of their subtlety and number, his confrontational pas de deux with modernity outgrace even Chaplin's marvelous Man-vs.-Machine allegories in Modern Times.

Also, today Chaplin often strikes us as oversentimental, maudlin even. That's not to downplay his genius at all, though there's something about Keaton's restrained, underplayed determination as he faces each new obstacle that feels refreshingly timely. The Little Tramp was Chaplin's "Everyman," self-consciously created to embody all people from all times. The character's longevity is a testimony to that universality. But it's Keaton's innocent yet unflappable achiever we more identify with. As Keaton himself put it, "Charlie's tramp was a bum with a bum's philosophy. Lovable as he was, he would steal if he got the chance. My little fellow was a workingman, and honest." We feel for the Tramp, but we want to be like Keaton.

Of all the films given the label "classic" over the years, The General stands solidly within the much smaller subset that actually deserve the label. The General ranks high on such lists as the top films of the silent era. In 1955, the Museum of Modern Art in New York paid tribute to United Artists. At the event, only The General was so clamored for that MOMA showed it twice. Every ten years the august British film magazine Sight and Sound's international critics survey votes for the ten best films ever made. The General made the cut in 1972 and 1982, and still fares very well in the most recent poll, 2002. In 1989 the Library of Congress officially recorded the film's status as a national treasure by placing it among the first films voted onto the National Film Registry. In 1999, Buster ranked number 35 in Time-Life magazine's tally of the century's top 100 actors. The American Film Institute placed The General on its "100 Years, 100 Laughs" roster and Buster among the century's top 25 actors.

Of all the films given the label "classic" over the years, The General stands solidly within the much smaller subset that actually deserve the label. The General ranks high on such lists as the top films of the silent era. In 1955, the Museum of Modern Art in New York paid tribute to United Artists. At the event, only The General was so clamored for that MOMA showed it twice. Every ten years the august British film magazine Sight and Sound's international critics survey votes for the ten best films ever made. The General made the cut in 1972 and 1982, and still fares very well in the most recent poll, 2002. In 1989 the Library of Congress officially recorded the film's status as a national treasure by placing it among the first films voted onto the National Film Registry. In 1999, Buster ranked number 35 in Time-Life magazine's tally of the century's top 100 actors. The American Film Institute placed The General on its "100 Years, 100 Laughs" roster and Buster among the century's top 25 actors.

It's telling that the two most inventive actor-writer-directors Hollywood has ever produced, Keaton and Chaplin, in their heyday worked side by side but never together. One difference between these equal-yet-separate geniuses is that Chaplin was a stubbornly 19th-century Victorian making movies in, but unable to fully acclimate to, a whole new 20th century. Keaton, on the other hand, was a Machine Age modernist who grasped the world of Model T's and hand-cranked movie cameras as his toybox. Both are enjoying a boom of popular rediscovery in recent years. Although the DVD market has a lot to do with that, we can't help but suspect that — while both awe us and make us laugh — Chaplin speaks to our sense of nostalgia the way Dickens does, and Keaton connects with us as a fellow modernite. Who among us can't identify with his small, straight-backed figure standing atop his speeding engine, leaning forward as if his shoes are nailed to the roof, shading his eyes and gazing into the onrushing distance, wondering what the hell's coming next?

The DVD

Once again, film preservationist David Shepard and Image Entertainment have joined forces to bring us a best-yet presentation of essential classics from the silent screen. Shepard's work is always of interest to lovers of the great old stuff, as we've seen with new releases of silent-comedy compilations (The Best Arbuckle/Keaton Collection,

Slapstick Encyclopedia, and Slapstick Masters), as well as dramatic features such as Nosferatu, The Lost World, Dr. Mabuse, and The Sheik. Shepard's comedy creds also extend to Kino's 11-disc The Art of Buster Keaton and Image's six-disc series of Chaplin's Essanay and Mutual comedies, boxed sets that are gotta-have standard-bearers. Now this double-feature release of The General and Steamboat Bill, Jr. gives us another reason to thank Shepard and Image. Both films look better than they ever have on home video. The General in particular is, in a word, stunning.

Plus, as with the Slapstick Masters disc, Shepard augments these new editions with brand new Dolby Digital 2.0 musical scores from The Alloy Orchestra, the most eclectic and eccentric — and brilliant — film re-scorers working. This Boston-based trio possesses the uncanny ability to be hip, odd, clever, raucous, delicate, or playful while simultaneously showing respect and affection for the films we're watching. Their nontraditional percussive, quirky orchestrations are action- and scene-tailored while avoiding the temptations of "old-timey" clichés or "postmodern" Philip Glass-style avant-garde ambiguities. Their scores are thoroughly modern but aren't likely to ever feel frozen into a definable now. In 1999 Entertainment Weekly listed them among "The 100 Most Creative People in Entertainment."

Visually, the prints here exhibit — as Shepard noted in an email to me — the remarkable advances in telecine mastering that have occurred since he last worked on these films for Kino nine years ago. While the Kino discs remain very good, these new Image editions are superior. They show greater cleanliness, clarity, definition, and black-and-white tone balance. The General comes from a better source master print alogether, I'm assuming a 35mm print struck from an original camera negative. (Shepard, under a contractual non-disclosure agreement, is mum on this point and don't think I didn't try.) Running speeds are adjusted properly for both The General (76 minutes at 26 frames per second) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (70 minutes at 24 frames per second).

Visually, the prints here exhibit — as Shepard noted in an email to me — the remarkable advances in telecine mastering that have occurred since he last worked on these films for Kino nine years ago. While the Kino discs remain very good, these new Image editions are superior. They show greater cleanliness, clarity, definition, and black-and-white tone balance. The General comes from a better source master print alogether, I'm assuming a 35mm print struck from an original camera negative. (Shepard, under a contractual non-disclosure agreement, is mum on this point and don't think I didn't try.) Running speeds are adjusted properly for both The General (76 minutes at 26 frames per second) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (70 minutes at 24 frames per second).

Furthermore, The General well-done sepia tone tinting enhances the visual impact without being oversaturated or jarring. Flesh tones look like flesh tones, and it's achieved subtly, with no "painted in" garishness.

Bottom line: I've never seen The General look so visually fresh and rich before this edition, which is now the one that'll get slid into the player whenever I want to show the film to benighted friends.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. comes untinted, but it too is cleaner, sharper, and benefits from recent improvements in film preservation and DVD authoring. The source master is in very good condition. Its black-and-white gray tones are smooth and solid.

The Alloy Orchestra scores are likewise the new soundtracks of choice for residential Keatonfests. Both are full-bodied with strong dynamic range and digital-to-digital clarity. The all-new orchestration for The General brings out the narrative's darker tones, treating it more as a suspenseful chase thriller than as a slide-whistle-and-slapstick comedy. It's a bold yet appropriate choice. The score supports both the dramatic and comic elements without (as typical "silent film" soundtracks tend to do) shirking the former and overemphasizing the latter. Alloy understands that Keaton's painstakingly crafted comedy needs no underlining or boldfacing from them. (On the Slapstick Masters collection, their score for Chaplin's Easy Street also lifts up that film's darker currents.) They are at their best with scores honed over many live performances in concert with the respective movies, as is the case for both The General and Steamboat Bill, Jr. In Steamboat they cut loose for some uptempo fun, highlighting a bluesy harmonica and banjo motif. The cyclone scene is a percussionist's party mix.

This new release of two essential silent-screen classics is a must-see for those who already consider themselves Keaton fans and for anyone who'd like to see what all the fuss is about. Tell 'em Jackie Chan and Sylvester Stallone sent you.

—Mark Bourne

- Black and white with color tinting

- Full-screen (1.33:1)

- Single-sided, single-layered disc (SS-SL)

- Dolby 2.0 monaural

- Keep-case

![[box cover]](../../reviewimgs/b/busterkeatondf.jpg)

In hot pursuit, Johnnie clambers over the General's fuel tender onto the flatcar holding a cannon he acquired en route. He measures a handful of gunpowder in pinches, then tamps it down, loads the cannonball, lights the fuse, and returns to the engine's control cab. The cannon fires and the cannonball arcs (rather delicately) to his feet in the cab. Giving it that famous deadpan Keaton look, he rolls the cannonball off the speeding train shortly before it explodes.

In hot pursuit, Johnnie clambers over the General's fuel tender onto the flatcar holding a cannon he acquired en route. He measures a handful of gunpowder in pinches, then tamps it down, loads the cannonball, lights the fuse, and returns to the engine's control cab. The cannon fires and the cannonball arcs (rather delicately) to his feet in the cab. Giving it that famous deadpan Keaton look, he rolls the cannonball off the speeding train shortly before it explodes.

Of all the films given the label "classic" over the years, The General stands solidly within the much smaller subset that actually deserve the label. The General ranks high on such lists as the

Of all the films given the label "classic" over the years, The General stands solidly within the much smaller subset that actually deserve the label. The General ranks high on such lists as the  Visually, the prints here exhibit — as Shepard noted in an email to me — the remarkable advances in telecine mastering that have occurred since he last worked on these films for Kino nine years ago. While the Kino discs remain very good, these new Image editions are superior. They show greater cleanliness, clarity, definition, and black-and-white tone balance. The General comes from a better source master print alogether, I'm assuming a 35mm print struck from an original camera negative. (Shepard, under a contractual non-disclosure agreement, is mum on this point and don't think I didn't try.) Running speeds are adjusted properly for both The General (76 minutes at 26 frames per second) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (70 minutes at 24 frames per second).

Visually, the prints here exhibit — as Shepard noted in an email to me — the remarkable advances in telecine mastering that have occurred since he last worked on these films for Kino nine years ago. While the Kino discs remain very good, these new Image editions are superior. They show greater cleanliness, clarity, definition, and black-and-white tone balance. The General comes from a better source master print alogether, I'm assuming a 35mm print struck from an original camera negative. (Shepard, under a contractual non-disclosure agreement, is mum on this point and don't think I didn't try.) Running speeds are adjusted properly for both The General (76 minutes at 26 frames per second) and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (70 minutes at 24 frames per second).